Service workers

Have you been in a situation where you browsed a website for a period of time, then came back to it, and all of your progress was lost? Maybe it was some marketplace, where you added a lot of items to your shopping cart in preparation for an annual family picnic, and you had to work around a sea of nitpicks and preferences of your relatives to formulate this list, just for it to disappear because you lost internet connection?

9 times out of 10, a situation like this is a sign that the web application is lacking offline support, for example, caching through service workers.

Many of the world’s most reliable web experiences rely on service workers — often without users even realizing it.

- Twitter Lite uses a service worker to cache core assets and user data, allowing the app to load instantly on repeat visits and stay usable even with spotty mobile connections. The result? A 30% reduction in bounce rate and a 75% increase in tweets sent from poor-network regions.

- Google Docs employs offline caching and background synchronization, letting users continue editing their documents when disconnected. Once the connection is restored, the service worker synchronizes the changes seamlessly with Google’s servers.

- Spotify Web Player caches the UI shell and recently played tracks so users can still browse their playlists and resume playback when the network drops momentarily.

What are service workers?

Service workers are background scripts that run in the browser and act as a programmable proxy between a web application and the network. They intercept network requests, manage caching, and enable features like offline access, push notifications, and background synchronization. In simple terms, they give developers fine-grained control over how content is delivered to users, regardless of network conditions.

This matters because the modern web isn’t always reliable. Users may lose Wi-Fi, run into poor cellular coverage, or go completely offline while still expecting their apps to remain usable. Without service workers, most websites simply fail in these scenarios, leaving users with broken pages or blank screens. With service workers, developers can design resilient experiences—serving cached content, queuing actions for later, and ensuring apps remain functional even when the network doesn’t cooperate.

This technology is so powerful that some prominent speakers in the web development world, like Kyle Simpson, suggest that every web application needs an offline caching functionality, implemented via service worker or other relevant caching strategy:

“This is what I'm talking about. This is why I say that every single website on the Internet needs to change the way they think about the information that is presented to people and the experiences. And they're not always gonna be perfect, but they oughtta not just be blank unusable screens.” - Kyle Simpson, The Case for Service Workers

How do service workers function?

At their core, service workers are scripts that the browser runs in the background, separate from the main web page. They don’t have direct access to the DOM, but they can listen for specific events (like network requests, push messages, or sync operations) and decide how to handle them. This also means that service workers handle background tasks like caching and network requests without blocking the main JS thread — though they’re not designed for heavy computations or continuous processing.

The lifecycle of a service worker has three main phases:

- Registration – Your website’s JavaScript registers the service worker file with the browser.

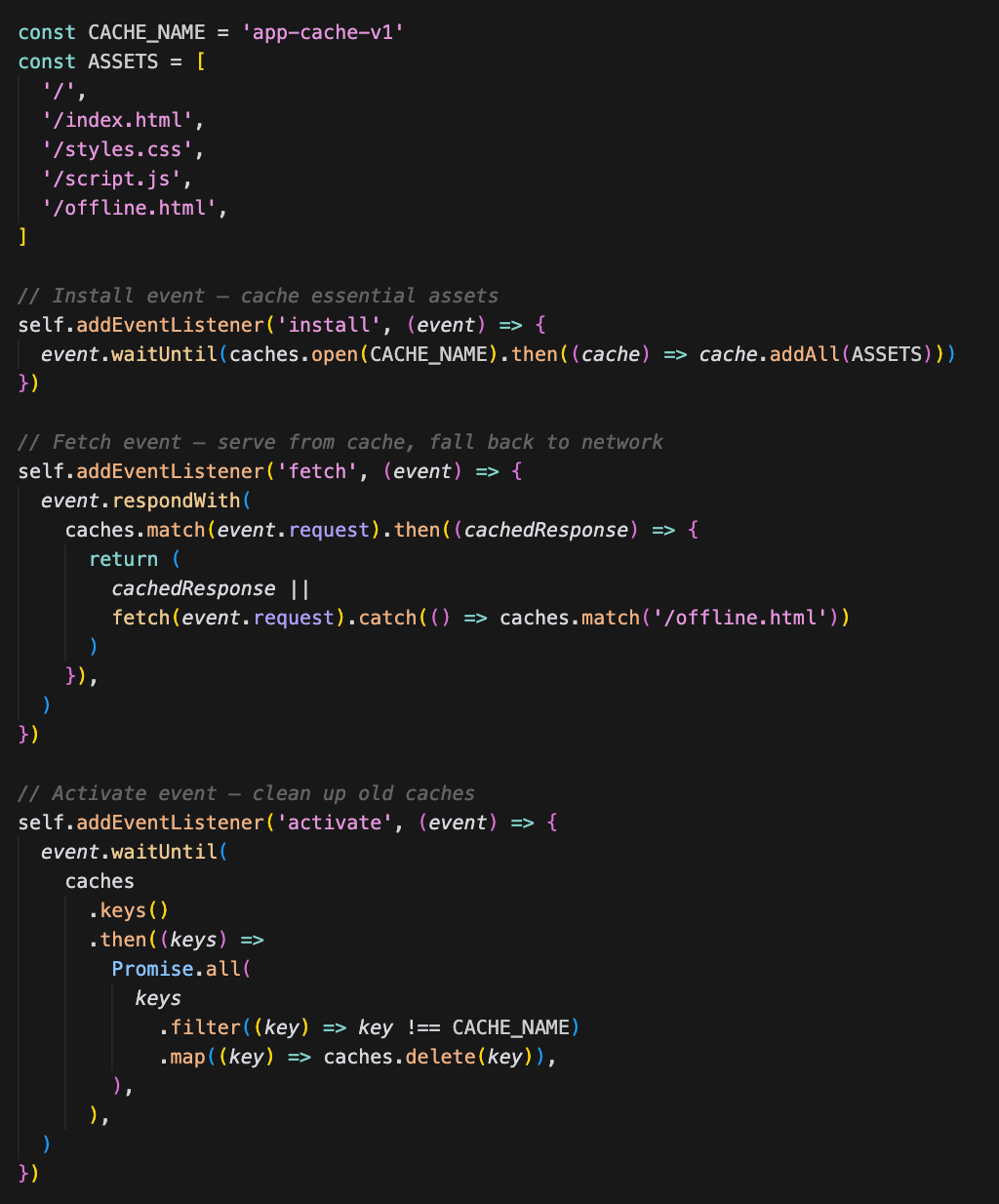

- Installation – The service worker is downloaded and installed. This is where you usually cache essential files (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images) so they’re ready for offline use.

- Activation – Once installed, the service worker takes control of the page. From here, it can intercept requests, serve cached responses, or fetch fresh data from the network.

Service workers are event-driven: they wake up only when something relevant happens. For example:

- The

fetchevent lets you intercept network requests and respond with cached content or fall back to the network. - The

syncevent allows you to retry actions (like form submissions) when the user comes back online. - The

pushevent enables push notifications, even when the site isn’t open.

Unlike normal JavaScript, service workers are designed to be resilient. They don’t block the main thread, and they persist across page reloads. This makes them ideal for improving reliability and user experience.

How do we create one?

Implementing a service worker is as simple as it gets. You only need two files: your main JavaScript that registers the worker, and the service worker script itself.

1. Register the worker

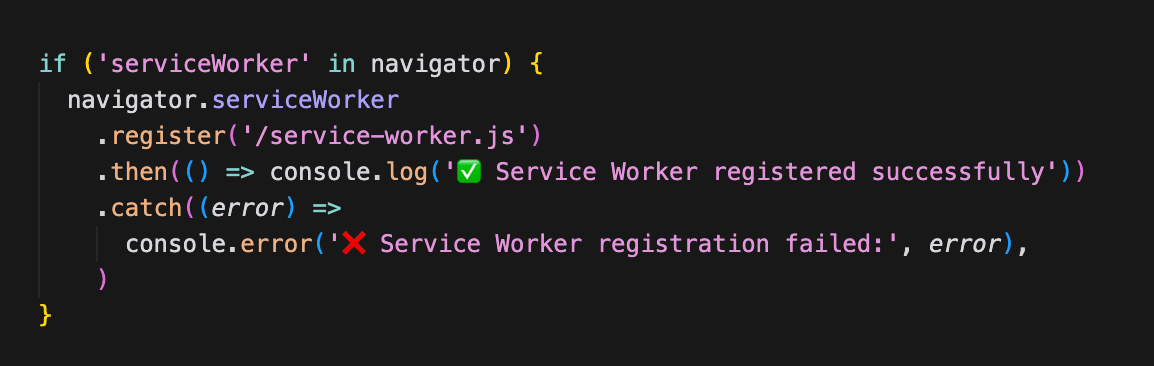

Place this code in your main JavaScript file, such as main.js:

service-worker.js file in the background.2. Create the worker

In the root of your project, create a file named service-worker.js:

3. Test it out

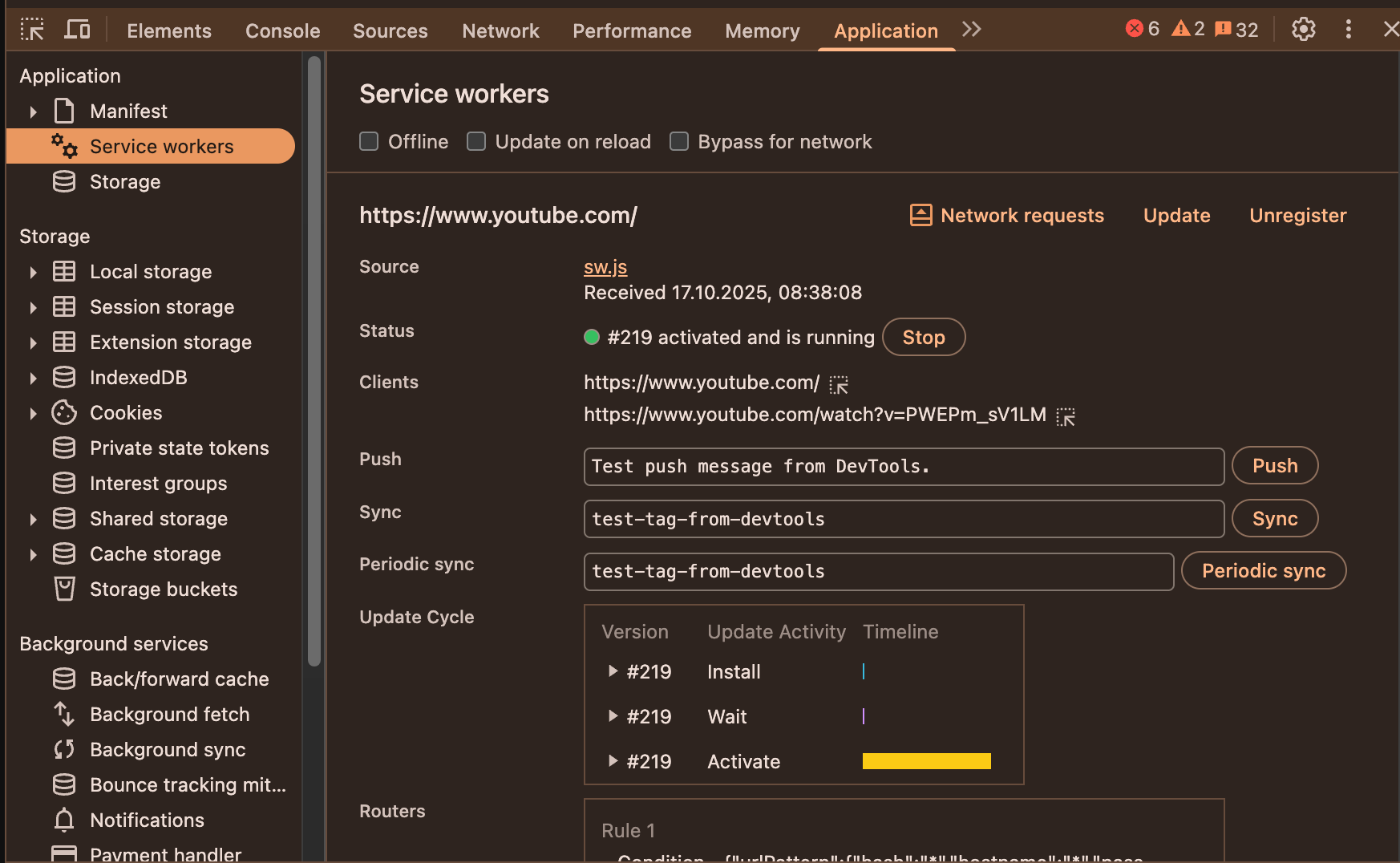

- Serve your app over HTTPS (required for service workers).

- Open DevTools → Application → Service Workers.

- Check “Offline” and reload the page — it should still load using cached data.

With just a few lines of code, your app now loads instantly on repeat visits and remains usable even when the network goes down.

Common caching strategies with service workers

One of the most powerful aspects of service workers is the ability to decide how and when resources are fetched. Developers use different caching strategies to balance speed, freshness, and reliability depending on what kind of content the application serves.

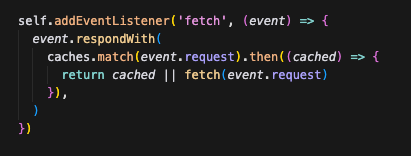

A cache-first strategy loads content directly from the cache if it’s available and only falls back to the network if it’s missing. It’s ideal for static assets such as logos, fonts, or CSS files that rarely change.

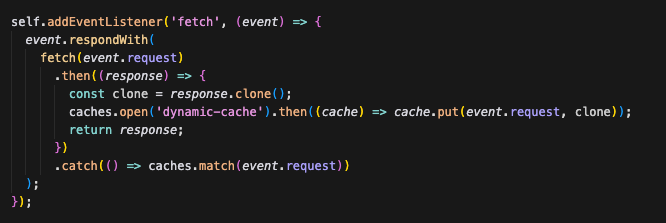

A network-first strategy tries to fetch fresh content from the network but uses the cache as a fallback when the connection fails. It’s a good fit for dynamic content like news feeds or user data.

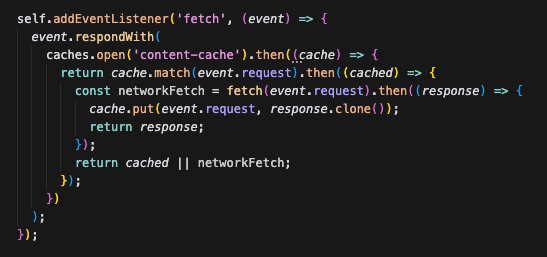

The stale-while-revalidate approach serves cached data immediately for fast load times while fetching a newer version in the background to update the cache for the next visit.

In practice, most applications use a mix of these strategies—cache-first for static assets, network-first for frequently changing data, and stale-while-revalidate for everything in between. Choosing the right combination is key to making a web app feel instant and reliable, even when the network isn’t.

Modern Approaches and Tools

Building a service worker from scratch is a great way to understand the fundamentals, but most modern projects rely on frameworks and libraries that simplify offline functionality, caching, and updates.

Here are some of the most widely used tools and ecosystems for managing service workers today:

Workbox (by Google)

A set of production-ready libraries and build tools that make implementing caching and routing strategies much easier.

Workbox automates complex tasks like cache versioning, background updates, and precaching assets. It’s often integrated with Webpack, Rollup, or Vite, and is used under the hood by many PWA tools.

Vite Plugin PWA

A plugin for Vite that turns any project into a Progressive Web App with minimal configuration.

It automatically generates a service worker and a web app manifest, handles asset precaching, and supports background updates using Workbox internally. Ideal for modern frameworks like React, Vue, and Svelte.

PWABuilder

A Microsoft project that provides a graphical interface for converting any existing website into a Progressive Web App.

It automatically generates the necessary service worker, manifest, and icons — great for developers who want to “PWA-ify” an existing project quickly.

Summary

Service workers have become an essential part of creating resilient, modern web applications. They allow developers to bridge the gap between online and offline experiences by caching content, intercepting network requests, and synchronizing data in the background. From social media platforms like Twitter to productivity tools like Google Docs, many of today’s most seamless web experiences rely on service workers to keep users connected — even when the network isn’t.

By understanding how service workers function, implementing basic caching strategies, and leveraging modern tools like Workbox, Vite PWA, or PWABuilder, developers can significantly improve both the reliability and performance of their applications. In an era where connectivity can’t always be trusted, offline support is no longer a luxury — it’s a cornerstone of great user experience.

Member discussion